Chapter 2 Condensing data with numerical summaries

James Bond: [to Vesper] Why is it that people who can’t take advice always insist on giving it?

One of the roles of a data scientist is to condense large amounts of information into a few key summaries. There are many possible choices when simplifying data and it is certainly not the case that “one size fits all”. In this chapter, we will look at standard measures of location and spread, which are the building blocks for many statistical and machine learning algorithms. We discover that some measures fit naturally into a big data scenario while others do not.

2.1 Mathematical notation

Before we can talk more about numerical techniques we first need to define some basic notation. This will allow us to generalise all situations with a simple shorthand.

Very often in statistics we replace actual numbers with letters in order to be able to write general formulae. As discussed earlier, we generally use a single upper case letter to represent our random variable and the lower case to represent sample data, with subscripts to distinguish individual observations in the sample. Amongst the most common letters to use is \(x\), although \(y\) and \(z\) are frequently used as well. For example, suppose we ask three people how many mobile phone calls they made yesterday. We might get the following data: 1, 5, 7. If we take another sample we will most likely get different data, say 2, 0, 3. Using algebra we can represent the general case as \(x_1\), \(x_2\), \(x_3\):

| 1st sample: | 1 | 5 | 7 |

| 2nd sample: | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| \(\vdots\) | \(\vdots\) | \(\vdots\) | \(\vdots\) |

| typical sample: | \(x_1\) | \(x_2\) | \(x_3\) |

This can be generalised further by referring to the random variable as a whole as \(X\) and the \(i\text{th}\) observation in the sample as \(x_i\). Hence, in the first sample above, the second observation is \(x_2=5\) whilst in the second sample it is \(x_2=0\). The letters \(i\) and \(j\) are most commonly used as the index numbers for the subscripts.

The total number of observations in a sample, that is the sample size, is usually referred to by the letter \(n\). Hence in our simple example above \(n = 3\).

The next important piece of notation to introduce is the symbol \(\sum\). This is the upper case of the Greek letter \(\sigma\), pronounced ‘’sigma’‘. It is used to represent the phrase ’sum the values’. This symbol is used as follows \[ \sum_{i=1}^n x_i = x_1 + x_2 + \dots + x_n. \] This notation is used to represent the sum of all the values in our data (from the first \(i = 1\) to the last \(i = n\)), and is often abbreviated to \(\sum x\) when we sum over all the data in our sample.

2.2 Measures of location

These are also referred to as averages. In general terms, they tell us the value of a “typical” observation. There are two measures which are commonly used: the mean and the median. We will consider these in turn. When these are obtained from a sample of data, rather than the entire population, we often prefix with the word “sample”.

2.2.1 Sample mean

One of the most important and widely used measures of location is the (arithmetic) mean, more commonly known as the average \[ \bar x = \frac{x_1 + x_2 + \ldots + x_n}{n} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n x_i \] where \(x_i\) are our data points and \(n\) is the sample size, i.e. the number of data points in our sample. So if our data set was \(\{0,3,2,0\}\), then \(n=4\). Hence, \[ \bar x = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n x_i = \frac{0 + 3 + 2 + 0}{4} = 1.25 \;. \] In statistics, it is common to use a potential bar over a variable to denote the mean.

Why do we say “sample mean” instead of just mean? In statistics we make the distinction between the population mean (the true value) and the estimate mean. To differentiate between the population and sample means, we use μ and \(\bar x\) respectively.

Statistics uses the sample to inform us about the population.

Example: The beauty data set

The beauty data set contains results for 463 classes. After loading the data set into R, we can extract a particular column using the dollar operator

## Attractiveness score

beauty$beauty

## Number of students per class

beauty$studentsWe can use the built-in function mean() to calculate the average attractiveness score and class size

## Attractiveness score (normalised)

mean(beauty$beauty)

#> [1] -0.0883

## Number of students per class

mean(beauty$students)

#> [1] 55.22.2.2 Sample median

The median is occasionally used instead of the mean, particularly when the data have an asymmetric profile or when there are outliers (as indicated by graph, perhaps). The median is the middle value of the observations when they are listed in ascending order. It is straightforward to determine the median for small data sets. For larger data sets, the calculation is more easily done using a computer package such as R.

Ranked observations are denoted as \(x_{(1)}, x_{(2)}, \ldots, x_{(n)}\). The sample median is defined as: \[ \text{Sample median} = \begin{cases} x_{(n+1)/2}, & n \text{ odd;} \\ \frac{1}{2}x_{(n/2)} + \frac{1}{2} x_{(n/2+1)}, & n \text{ even}\;. \end{cases} \]

The median is less sensitive to outliers than the sample mean, but has less useful mathematical properties.

For our simple data set \(\{0, 3, 2, 0\}\), to calculate the median we re-order it to: \(\{0, 0, 2, 3\}\); then take the average of the middle two observations, to get 1.

Example: The beauty data set

R has a built-in function called median() that we can use to calculate sample median. We’ll use the same variables as previous

median(beauty$beauty)

#> [1] -0.156

median(beauty$students)

#> [1] 29Notice that the mean and median beauty scores are approximately the same; this implies that the data are roughly symmetric. However the class size values differ: \(\bar x = 55\) and the median is \(29\). This is because the class sizes are skewed; there are many more large values than smaller values.

The classic case of where it can be misleading to use the mean, is income. Here a few very rich individuals can dominate the statistic.

2.3 Measures of spread

A measure of location is insufficient in itself to summarise data as it only describes the value of a typical outcome and not how much variation there is in the data. For example, the two datasets 10, 20, 30 and 19, 20, 21 both have the same mean (20) and the same median (20). However the first set of data ranges considerably from this value while the second stays very close. They are quite clearly very different data sets. The mean or the median does not fully represent the data. There are three basic measures of spread which we will consider: the range, the inter–quartile range and the sample variance/standard deviation.

2.3.1 Range

The range is easy to calculate. It is simply the largest minus the smallest.2 \[ \text{Range }= x_{(n)} - x_{(1)} \] where \(x_{(n)}\) is the largest value in our data set and \(x_{(1)}\) is the smallest value. So for our data set of \(\{0,3,2,0\}\), the range is \(3-0=3\). It is very useful for data checking purposes, but in general it’s not very robust.

There are two problems with the range as a measure of spread. When calculating the range you are looking at the two most extreme points in the data, and hence the value of the range can be unduly influenced by one particularly large or small value, known as an outlier. The second problem is that the range is only really suitable for comparing (roughly) equally sized samples as it is more likely that large samples contain the extreme values of a population.

Example: OKCupid

Starting any analysis it’s a good idea to calculate the range of the variables. It’s a straightforward way of ensuring everything is correct. For example, the range of ages in the OK Cupid data set is

range(cupid$age)

#> [1] 18 110Perhaps a little on the high side?

2.3.2 Sample variance and standard deviation

In statistics, the mean and variance are used most often. This is primarily because they have nice mathematical properties, unlike the median. The sample variance, \(s^2\), is defined as \[ s^2 = \frac{1}{n-1} \sum_{i=1}^n (x_i - \bar x)^2 \] Essentially we are measuring the difference between the sample mean, \(\bar x\), and each observation in turn. By squaring the difference, we avoid positive and negative values cancelling.

The formula can be rewritten as \[

s^2= \frac{1}{(n-1)} \left\{ \left(\sum_{i=1}^n x_i^2\right) - n \bar x^2 \right\} \;.

\] The second formula is easier for calculations.3 However \(\sum x^2\) becomes very large as \(n\) increases. This could lead to a potential loss of precision, in practice we would use \[

s^2= \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{x_i^2}{n-1} - \left(\frac{n}{n-1}\right) \bar x^2 \;.

\]

For our toy data set, \(\{0,3,2,0\}\), we have \[

\sum_{i=1}^4 x_i^2 = 0^2 + 3^2 + 2^2 + 0^2 = 13.

\] So \[

s^2 = \frac{1}{n-1} \left\{ \left(\sum_{i=1}^n x_i^2\right) - n \bar x^2

\right\} = \frac{1}{3} \left( 13 - 4 \times 1.25^2\right) = 2.25.

\] The sample standard deviation, \(s\), is the square root of the sample variance, i.e. for our toy example \(s = \sqrt{2.25} = 1.5\). The standard deviation is preferred as a summary measure as it is in the same units as the original data. However, it is often easier from a theoretical perspective to work with variances.

A rule of thumb for getting a feel for your data, is that approximately 95% of data is contained in the interval \[ \bar x \pm 2 \times s \] We’ll see in chapter 4 the mathematical underpinning for this rule.

If this was a “Maths class”, we would spend some time discussing why we divide by n − 1 and not n. If we had access to all of the population, we would use n. However, we don’t and to correct for that we use n − 1.

2.3.2.1 Example: R

R has built-in functions to calculate the standard deviation and variance respectively

sd(beauty$evaluation)

#> [1] 0.555

var(beauty$evaluation)

#> [1] 0.3082.3.3 Quartiles and the interquartile range

The upper and lower quartiles are defined as follows:

- \(Q_1\): Lower quartile = (\(n\)+1)/4\(^{\text{th}}\) smallest observation.

- \(Q_3\): Upper quartile = 3 (\(n\)+1)/4\(^{\text{th}}\) smallest observation.

We can linearly interpolate between adjacent observations if necessary. The interquartile range is the difference between the third and first quartile, i.e. \[ IQR = Q_3 - Q_1. \] Like the median, the IQR isn’t influenced by large values (outliers). However it is more computationally difficult to calculate.

2.3.4 Numerical examples

For the following data sets, calculate the inter-quartile range:

- \(\{5, 6, 7, 8\}\)

The lower quartile is the \(5/4 = 1.25^{\text{th}}\) smallest observation, i.e. \(x_{(1.25)}\). The value of \(x_{(1)} = 5\) and \(x_{(2)} = 6\). So the first quartile is one quarter of the way between \(x_{(1)}\) and \(x_{(2)}\), i.e a quarter of the way between 5 and 6, \[ x_{(1.25)} = x_{(1)} + 0.25 \times (x_{(2)} - x_{(1)}) = 5 + \frac{6-5}{4} = 5.25. \] Similarly, the upper quartile is the \(3 \times (4+1)/4 = 3.75^{\text{th}}\) smallest observation. So \[ x_{(3.75)} = x_{(3)} + 0.75 \times (x_{(4)} - x_{(3)}) = 7.75. \] Therefore, \[ IQR = 7.75 - 5.25 = 2.5. \]

- \(\{10, 15, 20, 25, 50\}\).

The lower quartile is the \((5+1)/4 = 1.5^{\text{th}}\) smallest observation, i.e. \(x_{1.5}\), so \[ x_{(1.5)} = x_{(1)} + 0.5 \times (x_{(2)} - x_{(1)}) = 12.5. \] Similarly, the upper quartile is the \(3 \times (5+1)/4 = 4.5^{\text{th}}\) smallest observation. So \[ x_{(4.5)} = x_{(4)} + 0.5 \times (x_{(5)}-x_{(4)}) = 37.5. \] Thus, \[ IQR = 37.5 - 12.5 = 15. \]

2.3.4.1 R example

The quartiles are special cases of percentiles:

- The minimum is the 0\(^{th}\) percentile

- \(Q_1\) is the 25\(^{th}\) percentile

- The median, \(Q_2\) is the 50\(^{th}\) percentile

- \(Q_3\) is the 75\(^{th}\) percentile

- The maximum is the 100\(^{th}\) percentile

The quantile() function calculate these values

quantile(cupid$age)

#> 0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

#> 18 26 30 37 110The R function has also has a probs argument where we can specify our own percentiles

## The middle 90%

quantile(cupid$age, probs = c(0.025, 0.975))

#> 2.5% 97.5%

#> 20 58

# Rule of thumb

mean(cupid$age) - 2*sd(cupid$age)

#> [1] 13.4

mean(cupid$age) + 2*sd(cupid$age)

#> [1] 51.2

There are actually (at least) 9 different versions of how to calculate quantiles (see ?quantile in R). The version described in these notes is type = 6 in R. Typically, the quantiles give approximately the same answer.

2.4 Streaming data

Streaming data is data that is generated continuously by multiple sources. Developing algorithms for dealing with streaming data is an active area of research, both statistically and computationally. Even though we’ve only covered a few statistics, some of them can be easily adapted to deal with streaming data while others can’t.

2.4.1 The mean and variance

Suppose we have observed \(k-1\) values and our current estimate of the mean is \(m_{k-1}\). A new observation, \(x_k\) arrives. How would we update our estimate? An obvious method is \[ m_k = \frac{(k-1) \times m_{k - 1} + x_k}{k} \] However this method isn’t numerically stable. Basically \((k-1) \times m_{k - 1}\) can get large and we’ll lose precision. Instead we should use \[ m_k = m_{k-1} + \frac{x_k - m_{k-1}}{k} \] We have a similar algorithm for the variance \[ v_k = v_{k-1} + (x_k - m_{k-1})(x_k - m_k) \] Again this algorithm is numerically stable.

2.4.1.1 Example: R

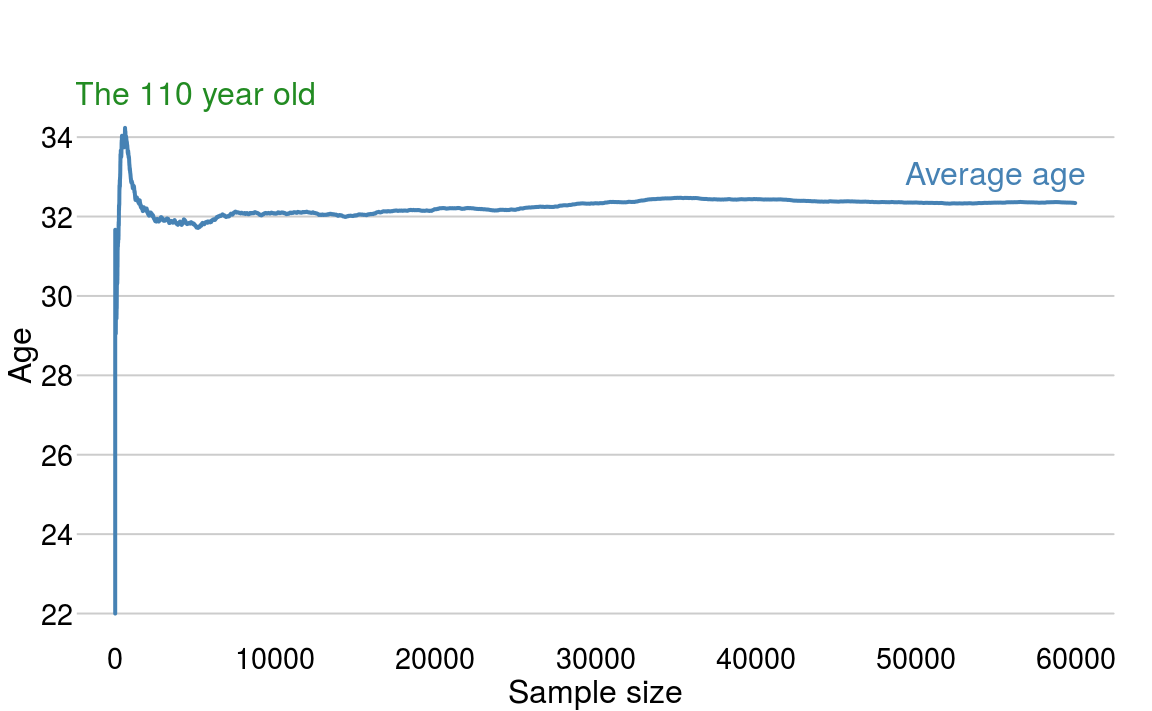

The OKCupid data set contains almost 60,000 individuals. Figure 2.1 plots the estimate of the mean age as we progress through the data set.

Figure 2.1: The estimate of the mean age as we progress through the data set.

After some variation in the first few observations, we quickly settle to a consistent estimate of the mean. The spike up to age \(34\) is due to the outlying age of \(110\)

2.4.2 The median and quantiles

In contrast to the mean keeping a running median is a non-trivial task. Essentially we need to maintain a sorted data structure containing the data. The key issues are storage cost of the data and retrieval time.

Relevant R functions

| Command | Comment | Example |

|---|---|---|

| mean | Calculates the mean of a vector | mean(x) |

| sd | Calculates the standard deviation of a vector | sd(x) |

| var | Calculates the variance of a vector | var(x) |

| quantile | The vector quartiles. | quantile(x, type = 6) |

| range | Calculates the vector range | range(x) |

When you get a new data set, calculating the range is useful when checking for obvious data-input errors.↩

The divisor is \(n-1\) rather than \(n\) in order to correct for the bias which occurs because we are measuring deviations from the sample mean rather than the ``true" mean of the population we are sampling from.↩